Offshore wind power: The under-explored opportunity to replace coal in Asia

Emerging Asian markets stand to benefit the most, as offshore wind could further reduce its over-reliance on emissions-intensive, expensive and inflexible imported coal-fired electricity.

Size matters

One of the major developments has been the dramatic growth in the scale of the rotor diameters of turbines. These have doubled from 80 to more than 164 metres, more than twice the length of an A380 Airbus, with capacity more than tripling to 4-6 MW today, from 1-2 MW in 2012.

Coupled with cross-industry learnings, offshore wind technology is already getting closer to matching the cost of energy of its onshore counterpart. With leading players like Orsted and Siemens betting on another doubling in size to 10-14 MW by 2024, the price decline will undoubtedly continue.

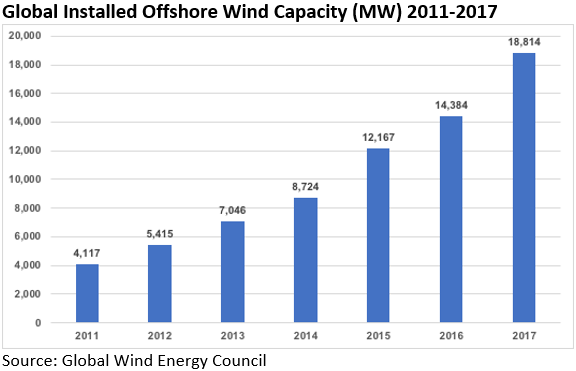

As a consequence, Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) projects the offshore wind power market to grow at 16% to reach a total global capacity of 115 GW by 2030, a sixfold increase from 2017.

While this estimation includes North America and Europe, it likely underestimates the enormous offshore wind potential of Asian economies.

Over the years, the growth in offshore wind power has predominantly come from Europe, with 84% of the total 18.8 GW of global offshore wind capacity installed in Northern Europe. 2017 saw a record 4.3 GW of offshore wind power capacity installed across nine markets.

Last year, three German offshore wind auctions totalling 1,380 MW were at a zero premium strike price, meaning the projects commissioned between 2023-2025 will offer electricity at prevailing wholesale market prices at that time.

Early in 2018, Netherlands awarded its first non-subsidised offshore wind tender of 750 MW to wind power developer Vattenfall.

Asia to take the baton from Europe

Over the past decade Europe has subsidised the research, development and deployment of offshore wind. Asian countries such as China, India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam are set to capitalise on Europe’s lead. In fact, BNEF suggests China, which had 2.7 GW at the end of 2017, will overtake the UKs current 6.8 GW in installed capacity by 2022.

High costs caused China’s initial 2020 target of 10 GW and other similar attempts to boost its offshore wind capacity to fall through, with less than 1 GW installed by 2015.

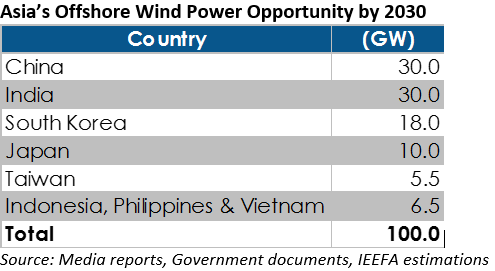

But the dynamics have since changed. China added 1.1 GW in 2017 and it is set to be a 3 GW per annum market by 2030 with installs peaking between 2022-2027, according to Wood Mackenzie’s MAKE consulting. China could install more than 30 GW of offshore wind power capacity by 2030 and provide cleaner power to its major economic hubs, most of which are located in coastal China.

In June 2018, the investment giant Macquarie Capital was reportedly looking to invest in South Korea’s 1 GW of offshore wind project with local developer Gyeongbuk. South Korea currently has a pipeline of 4 GW of offshore wind projects, that is part of the ambition to have 18 GW of offshore wind capacity installed by 2030.

Similarly, Taiwan and Japan has set targets of 5.5 GW and 10 GW respectively.

India’s ambitious 2027 renewable energy capacity target of 275 GW has put the country in the spotlight. It has set an offshore wind power capacity target of 5 GW by 2022 and 30 GW by 2030. April 2018 saw the Indian Ministry of New & Renewable Energy call for expressions of interest to develop a 1 GW offshore wind power project on its western coast.

Other Asian markets such as Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam are yet to formulate an offshore wind energy target. But, as they progress to build onshore wind power capacity, offshore developments should be on the cards.

As a whole, Asian economies have a cumulative ambition to build up to 100 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030. The opportunity is near limitless for capacity upscaling, particularly if floating wind is commercialised.

Lessons from Europe reflect that offshore wind power facilities could operate at up to capacity utilisation rate of 55%. By 2030, even if these countries are able to cumulatively achieve 70% of the 100 GW ambition, it could replace about 300-350Mt of coal annually – 35-40% of the current global seaborne trade.

The sector is still in an embryonic state in Asia, but with the right planning from developers and governments, offshore wind power will prove critical to an efficient energy mix sustaining reliable, cheaper and cleaner energy economies.

[Kashish Shah, Research Associate at IEEFA, contributed to this article as a co-author]

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed are solely of the author and ETEnergyworld.com does not necessarily subscribe to it. ETEnergyworld.com shall not be responsible for any damage caused to any person/organisation directly or indirectly.